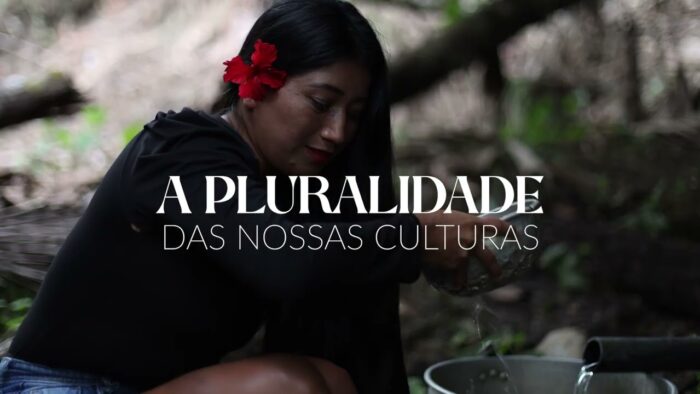

Os guaranis que fabricam pão para alimentar corpos e sonhos

Houve um tempo em que os guaranis da terra Tekoa Marangatu, no sul do Brasil, caçavam e coletavam para se alimentar. Hoje, a dieta é completamente diferente. A comida é comprada pelos indígenas ou doada pela população da cidade. Saíram as frutas, verduras, legumes e carnes; entraram os enlatados, biscoitos e outros produtos industrializados. A mudança na alimentação cobrou seu preço. Faltam vitaminas e proteína animal. Não há estatísticas, mas em conversas com o cacique e com os extensionistas rurais e sociais que trabalham na área, vêm à tona relatos de colesterol alto, sobrepeso, diabetes, problemas dentários e doenças de pele. “Depois de termos contato com os não indígenas, passamos a gostar dos alimentos produzidos por eles”, reconhece o cacique Ricardo Benete. “Mas queremos voltar a ser como antigamente, comer o que plantamos”, continua o líder guarani depois de mostrar os novos pomares, um pequeno apiário e as hortas que aos poucos estão surgindo na Tekoa Marangatu. O novo empreendimento do grupo é uma padaria onde os guaranis assarão pães e bolos saudáveis usando as frutas, verduras e raízes (como mandioca e batata-doce) disponíveis no local. A ideia é que os alimentos sirvam inicialmente para consumo das 45 famílias, tanto nas casas quanto na merenda da escola indígena. No futuro, eles querem também vender os produtos para obter uma nova fonte de renda. Hoje, a maior parte dos recursos da aldeia vêm da venda de artesanato nas cidades próximas, mas eles não suprem as necessidades da comunidade. Essa história evidencia os estados de nutrição e saúde dos indígenas depois do contato com o homem branco e os impactos positivos que um projeto pode ter se for algo nascido dentro do grupo. A padaria foi construída com apoio do Santa Catarina Rural, um programa do governo do estado e financiado pelo Banco Mundial, que beneficia 40.000 pequenos agricultores, incluindo mais de 1.200 famílias indígenas. “Foi importante incluir as comunidades indígenas rurais nesse trabalho por duas razões: porque elas produzem alimentos e porque o atendimento a elas passou a ser feito de forma integrada pelo governo”, explica Diego Arias, gerente do programa no Banco Mundial. A iniciativa conta com outros resultados positivos, como o da terra Xapecó, onde a etnia kaingang predomina entre as 1.350 famílias. Desde 2008, os indígenas vêm se especializando na criação de gado de leite. Setenta e nove famílias estão na atividade e conseguiram vencer os preconceitos do mercado, segundo o relatório de resultados do workshop Povos Indígenas e Projetos Produtivos Rurais na América Latina.